Cross Examination Questions: Essential Techniques, Tips and Secrets

mark anderson

mark anderson

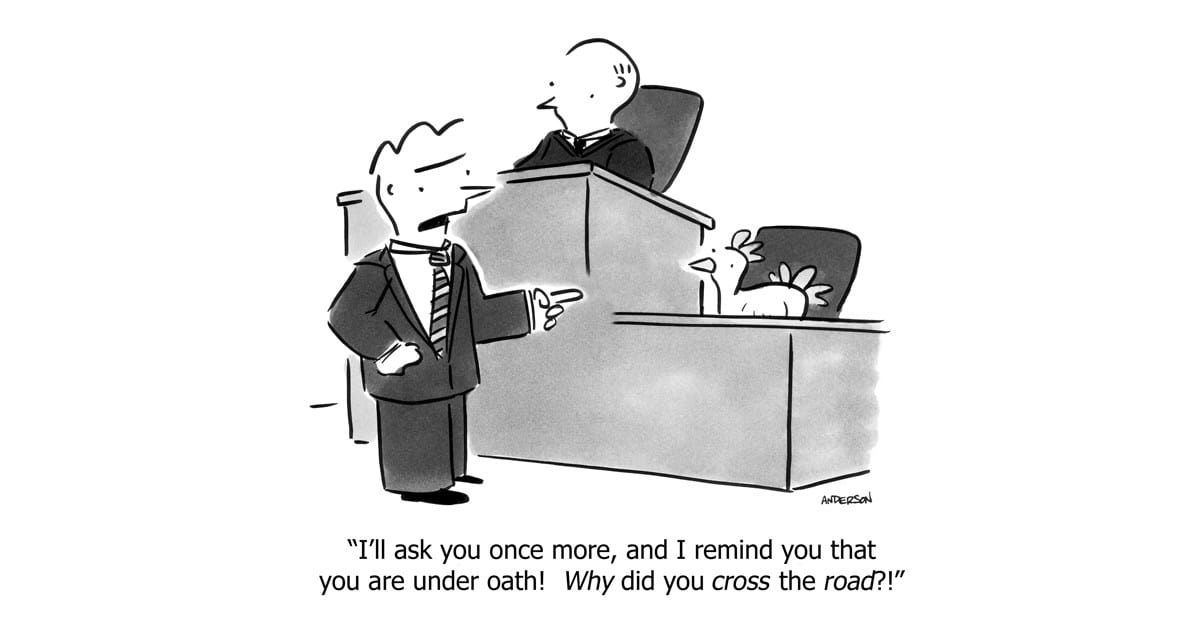

Cross-examination is one of the most adversarial, heated, and hostile parts of a trial. This is, of course, why it makes for the best scenes in courtroom dramas. And often what seasoned trial lawyers look forward to! But successful cross-examination is not about charisma and oratory skills; rather, effectively utilizing cross-examination questions is about excellent preparation, or hard work, and following some time tested and simple tips.

Since cross-examination is where you get to poke holes in your opposing party’s direct testimony and show the jury a witness isn’t as credible as they might have thought, it’s not the time to delve into the witness’s interpretation of the facts; rather, it’s the time for you to tell a story by obtaining the witness’s assent. Two books, The Art of Cross Examination by Francis L. Wellman and Cross-Examination: Science and Techniques by Pozner and Dodd are essential reading, and will serve you well.

Prior to beginning

Preparing for even a single line of questioning takes work, but therein lie the benefits. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to know the facts better than the witness and exactly what to do if they go off track or attempt to deceive.

In other words, you need to

- Review all the evidence: documents, transcripts, depositions, emails, etc.

- List the key evidence and facts for all issues and topics cross-referencing each source.

- Prepare the detailed sequences of questions for each fact and event you intend to prove.

- Determine your goal in developing your cross-examination plan.

Drafting the Questions

The rules of evidence should be your playbook as you enter cross-examination. It’s critical that you know your limitations, but you should take advantage of the few special tools offered to you on cross-examination and keep your focus on three specific tasks.

Ask only Leading Questions

“Isn’t it true that…?”

Leading cross-examination questions bring the courtroom dramas to life. An implied question mark at their end, in essence, they simply state a fact as a question!

What you what to avoid at all costs, is a non-leading, open-ended question: the type of question that begins with “how,” “what,” “when,” “why,” or “where”. A non-leading question gives a witness, especially an adverse one, a golden opportunity to reiterate their side’s theory of the case. You lose control and it’s a bad move.

Leading questions are prohibited on direct examination, but on cross-examination, the rules of evidence give you this gift. So make sure you take it! Your opposing party’s witness will be trying to tell their side of the story, so make sure they’re held to narrow yes or no questions as much as possible.

Avoid compound questions

Compound questions lack clarity and muddle the response you are trying to elicit. These wordy questions are not only apt to confuse the witness – or jury – but also lead to similar loss of control. Aim to establish only one fact per question.

Take this set for example:

A: Yes, I saw the man in a brown coat walking.

Now, this question has to be rehashed because the witness only admitted one of several facts he was asked. Whether a crafty move by a sharp witness, or simply inattentiveness, either way, it’s not helpful.

Have a specific goal for each question

Questions outside the scope of what was asked on direct (unless you are impeaching the witness and have a good faith basis for believing the questions to be true), shots in the dark, baseless allegations and harassing or trying to embarrass a witness with something irrelevant is purposeless questioning, a waste of time and an opportunity for a witness to score points against you. For example:

A:

This causes you all kinds of problems. Firstly, it gives the witness an opportunity to hurt the case. And secondly, such unfocused cross besides being dull and monotonous, and exasperating the jury, ends in rambling answers that often provide no information relevant to the case.

What should an attorney do instead?

Focus on a precise and controlled cross where they control the narrative and the order in which facts are presented which allows the witness no leeway. Disjointed cross-examination comes off as scattered and confusing. When you prove some or all of the key elements of your case using the other side’s witnesses it’s hard to lose.

Finally, follow the one principle that will serve you best: “Never ask a question you don’t already know the answer to.” This is the principle of cross-examination the overwhelming majority of effective lawyers hold dear to their hearts. And you should too.

In this clip from the classic comedy ‘My Cousin Vinny’, starring Joe Pesci and Marisa Tomei, Austin Pendelton, playing public defender John Gibbons, shows us why.

Should you cross-examine at all?

It’s not always in your best interest to cross-examine a witness. If they are credible, you may not get anything out of it. In fact, allowing the witness to keep testifying may bring out more information harmful to your case. Sometimes the best cross-examination, even of a critical witness after a lengthy direct examination, consists of only a question or two. Make sure too, when you’re cross-examining an expert witness that you understand the subject matter they’re testifying to, beforehand.

Decide whether to highlight favorable direct testimony or try to discredit the unfavorable

The witness coming off of direct has probably either helped or hurt your case. Juries inherently tend to distrust direct examinations; they tend to think witnesses will say anything to benefit their own case. In your cross-examination, you have the opportunity to either bolster what they said, or try to convince the jury it was not true. The questions you ask and the facts that you highlight will depend on which of these two types of testimony you’re going for. But remember, a witness may have inadvertently helped your case on direct, so if you give them another opportunity to present the same facts, you may elicit a, “Well that’s not really what I meant…” or “I don’t think I said it exactly that way…”. Either way, plan to lead the witness with short, precise questions.

Back to the facts

You need to know not only your angle of the case, but try to predict the adverse party’s as well. You won’t know everything they’re going to ask on direct, but you should think through as many possibilities in advance as you can so you’ll be able to think more quickly on your feet. Be careful not to draw out harmful information that wasn’t said in direct. This excerpt from Pattern Cross-Examinations by Walter Simpson illustrates the problem:

A: Yes, sir.

Q: You would agree with me that the word “excessive” is a subjective word that may mean different things to different people, right?

A: I suppose that is true.

Q: You did not have the forceps in your hands so that you could feel the amount of force being applied by Dr. Simon, isn’t that correct?

A: No, I didn’t.

Q: You would agree with me that the doctor must apply some force with the forceps in order to accomplish the delivery, wouldn’t you?

A: Yes, that is true.

Q: How could you possibly say then, Nurse Nelson, that Dr. Simon used excessive force in using the forceps to assist delivery?

A: Because he put his right foot up on the rail of the bed and leaned backwards as he was pulling on the baby’s head.

This mental image was harmful to the client and seemingly unknown to the attorney. It was not to the client’s benefit to keep pushing this question.

Impeach away

Your job is to convince the judge or jury that the witness is not reliable. This is one of the rare instances where you’re allowed to pull in character evidence to show that your witness has a reputation for untruthfulness. Has the witness contradicted themselves in a prior statement? Does their memory seem foggy? Do they have any underlying motivation or bias, such as a familial or monetary interest in the outcome of the trial? There are countless bases to impeach your witness. Remember though, to impeach a witness based on an earlier inconsistent statement, you have to recommit them. In other words, you have to get them to verify their earlier statement (that is, they have to agree it’s what they said) before you can challenge it. However, if your goal is both to elicit important testimony from an adverse witness as well as destroy their credibility on other points, then elicit the helpful testimony first.

Effective attacks on truthfulness come from showing a witness has testified inconsistently under oath. When testimony at trial is contradictory to testimony at deposition, such impeachment can be catastrophic to a jury’s willingness to believe that witness. In attacking truthfulness (as opposed to a witness’s reliability in recounting facts), each point of impeachment should be strong and only directly related to the key issues in the case. Focusing on minor points is ineffective and counter-productive.

Make the witness answer your question

There are a number of reasons why a witness may seem defensive or evasive. For most people, being cross-examined is stressful and high-pressure. They’re often being asked personal questions trying to highlight all their bad qualities – unpleasant by all means. They have also probably received direction from opposing counsel about what points to try to underplay. When the witness is avoiding, dodging or gives a rambling answer to a direct question, it’s your prerogative to get an answer.

You can repeat your question, directly ask the witness to answer your question, or rephrase the question and request it be answered in a yes or no format. As a last resort, you can ask the judge to intervene, but this tactic should be used rarely.

Anticipate objections and quickly get back on track

Some of the common trial objections that can come up during your cross include:

- Privileged

- Compound or double question

- Vague or confusing

- Hearsay

- Immaterial or irrelevant

- Speculative, among many other form objections

Because cross gives you so much latitude to discredit key witnesses or draw out harmful information, opposing counsel is quite likely to object to as much as possible to disrupt the flow of your questioning. It’s therefore important to get back on track by restating the question or pivoting to your next line of questioning, as appropriate.

It’s also possible for the judge’s tendencies on cross-examination to affect your outcome. Since the cross is a contentious time that tests the boundaries of evidentiary rules, there’s a lot of discretion at play. Certain judges may rule conservatively on objections, while some may be more active in directing the witness to get to the point. Knowing the judge’s mannerisms will help you estimate how much you can push the limits, or how much you should stay in your lane.

Be mindful of tone and whom you’re talking to

Since witnesses can range from medical experts to traumatized children, make sure your tone is appropriate and respectful. Remember, your ultimate audience is the fact finder. Make sure it’s clear to the jury what you’re trying to get out of the witness; sounding too smart or formal risks putting off the witness and/or the jury.

Learn the expert’s theories, and develop your own theory

When you are cross-examining an expert witness, you are most likely not going to have anywhere near the technical or scientific expertise that the witness does – that’s why they’re the expert. You must study the expert’s report, however, and develop an alternate theory. Is the expert biased? How much are they getting paid? Do they have some other interest in the outcome of the litigation? Are they really qualified? Is there a blaring error, or at least an inexplicable logical gap in their report? You may be able to show that the research is less conclusive than the expert is letting on, but you have to be able to frame it for the jury to follow. Like any other cross-examination, keep expert witnesses to “yes” or “no” questions, especially ones that support your theory of the case.

Knowing when to stop

Keeping the questioning as brief as possible, and trying to end on a high note is your ultimate goal. So, if you believe you’ve sufficiently highlighted the important facts or discredited the witness, close out gracefully and draw your conclusions in your summation.

Preparing

In preparing for an effective cross examination, either Wellman’s or Pozner and Dodd’s books will serve you well. Both are filled with useful tips, detailed examples and methods that you can and should utilize. However, in this crucial task, a reliable system for organization and preparation soon becomes vital. Mixed applications, notepads and loose pages can easily result in missed facts that should have been addressed – even if you have good indexing or a well thought out manual system. What’s missing is the ability to automatically cross-reference and link evidence, facts, events, and witnesses, to key issues – and the sheer volume of evidence and number of facts and events to keep track of even in smaller cases.

Litigation support software from MasterFile lets you stay on top of exactly that. It brings together all the building blocks of your case allowing quick access to facts, dates, times, issues, witnesses and evidence – in one intuitive platform. Its case timelines and event chronologies let you collaborate and easily share research and insight that strengthens your case analysis and your legal strategy, and help you to never miss a connection again.

Manage your evidence, disclosures, production, case chronologies and case analysis more efficiently and more effectively in MasterFile. Win more – and have an easier time doing so!

Learn more about how MasterFile helps you prepare for cross examination.